Director's cut of a review published in The Wire #335 (January 2012)

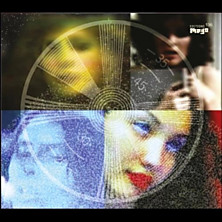

Mark

van Hoen

The Revenant Diary

Editions

Mego CD/LP

Time

is the alarming issue, the element most subject to the shearing

pressure of social contradiction today. As average working weeks

increase, we're enjoined ever more to indulge in colour-supplement

leisure activities (“get making those memories”, as a recent

advertising slogan had it). In the face of systemic crisis, we're

haunted by the vague sense that time's running out; simultaneously,

we seem to have more of it than ever – in abundant archives, in

multiplying ephemeral media of memory-inscription (Twitter, Facebook,

blogs). Like Blade Runner's

Roy, our memories press maddeningly on the present, bursting into the

body of music, blurring or sharpening their significances, at the

moment they threaten to disappear “like tears in the rain”. As

the archivists carry on their pursuits (witness the hauntological

barrel-scraping of the Found Objects blog and the continuing vogue

for 'austerity chic'), the quality of that time seems to matter

increasingly little, just so long as it's past.

The

latest solo album by former Seefeel member Mark van Hoen (who

previously worked under the name Locust) seems to come with the same

set of conceptual baggage as all the nostalgia-swollen albums of the

past few years. But there is immediately a disturbing spark. The

story goes: listening through his archive, van Hoen came across a

track made in 1982 by his adolescent self, setting off a recall of

even earlier recordings; in turn he was encouraged to try a more

primitive recording set-up, of the kind he started out with: 4-track

tape, minimal equipment. The potential dangers present themselves

immediately: soft-focus recreation of simpler times, the sonic

equivalent of the mid-life crisis car. From the first, though, he

avoids them: the beats are rough, cutting hi-hats and a loping kick

like distant depth-charges, frayed at the edges, synth-strings and

female vocal as if imported from from a horror film. Nowhere, in

fact, does the percussion become very sophisticated – as with his

often somewhat portentous 90s work, van Hoen seems defiantly to

occupy the only corner of electronica untouched by Techno and House's

seductions. There's something queasy and out-of-joint about the

mixing; it's as if van Hoen were adopting a deliberately broken

language, feeling out the possibilities in stuttering, cracked

versions of familiar gestures, of the slick, brooding digital

productions that have dominated his catalogue to date. (Notably,

where van Hoen sang on last year's Where Is The Truth, here

the voices are borrowed, though whether from vocalist Georgia Belmont

or sampled is hard to tell.)

This

lure of primitivism seems to lie behind much of the last few years'

fetishisation of analogue – think of the often clunky beats of

Ekoplekz's catalogue, or the laborious, semi-aleatoric methods of

Keith Fullerton Whitman's synth records. This partly evokes the

relationship one has with sound-making technology when just starting

out: the directness and simplicity with which one plays with sound,

but also the physical particularity of analogue – tape recorders

with their buttons that clunk, synths, drum-machines, guitars with

their knobs for settings and tone, turntables and the motion of

needles and record surfaces, all this that filled the adolescence of

musicians of a certain age. It's unsurprising that van Hoen seems

fascinated on this record by certain granular qualities of noise, the

kind of roughened grain (usually applied by him to the voice) often

arrived at by happy accident. The sonic account of adolescence in The

Revenant Diary is far more interesting than the simplified

version that lies at the core of, say, chillwave – and far truer to

the difficulty of adult being. The perspective on the narrowness, the

hateful, humiliating, unnecessary agonies of adolescence that

hindsight purchases does so at the expense of its sense of

possibility, of a meaning that saturates every second (and that

spills out into overfilled diaries), from which it is in reality

inextricable; van Hoen maintains this desire, this danger –

adolescence as a wager, a roll of the dice.

Van

Hoen's position is complicated by one of the narratives hiding behind

The Revenant Diary: he was adopted as a child, a fact that

became the sort-of subject matter of Where Is The Truth. To be

suddenly dispossessed of a past, to have what lies at the centre of

self-image disturbed: this, in fact, is our condition today. “Don't

look back” warns the voice at the centre of the eponymous track –

not because the past is somewhere to get stuck, preventing the

subject from constructing the future (the traditional argument

against nostalgia) but because its truth-content is put under

question, if not hollowed-out. Van Hoen, notably, although working

with an earlier set-up and methodology, doesn't use particular

textural or pop-idiomatic signifiers (as hypnagogic pop does). In

this respect (as in most others) the beatless tracks are most

interesting: “37/3d” is a minimal construction of static burbles,

pointillist synth and backward, overlapping voice; “No Distance”

is the kind of haunted sequencer architecture explored on Oneohtrix

Point Never's early releases; “Holy Me” is 9 and a half minutes

of solo multi-tracked voice, I Am Sitting In A Room as remixed

by Oval. There's a sense of suspension in these tracks: a glittering

sadness, but a refusal of the particularising pathos of meaning,

which pins sound to a particular time.

Diaries

sought to organise life: month after month, year after year,

experience is recorded. The present nostalgia for analogue media

(tapes, vinyl records, chemical photography) and all its – as often

as not trashy – content is also a longing for a moment when time

could be experienced this way: coherent, slowly accumulative, humanly

meaningful, experienced in the “pseudo-cyclical” (the phrase is

from Guy Debord) passage of seasons and festivals. What is swiftly

becoming clear is how useless nostalgia is to getting a grip on our

own sense of time in the ongoing crisis – not least because it

leaves us with the alienated figments of time, emptied of

historicity, of what might be meaningful to our present. The

Revenant Diary, spooking us in its best moments with the

unremembered fragments of van Hoen's self, confounds all of that.

It's a very good start.

No comments:

Post a Comment